The Last Time I Cooked for Sergio Leone

Last Suppers

The last time I cooked for Sergio Leone it ended in a bloodbath.

Dust blew in through the carriage windows, mingled with the cigar smoke and hung there in a fug. The train rattled along the iron tracks as it cut its way through the barren landscape of Almeria. The continual jangling and jolting made the cooking of señor Leone’s lunch difficult to say the least. The only way I could keep the pan of water on the tiny gas ring was by tying one handle to the window catch with the thong from my gun belt and wedging the other handle in place with the barrel of my revolver. Difficult and dangerous. But the great man was hungry, so what could I do?

We had been in the carriage for hours. Blondie, Tuco and Angel Eyes sat watching each other at a big long table.

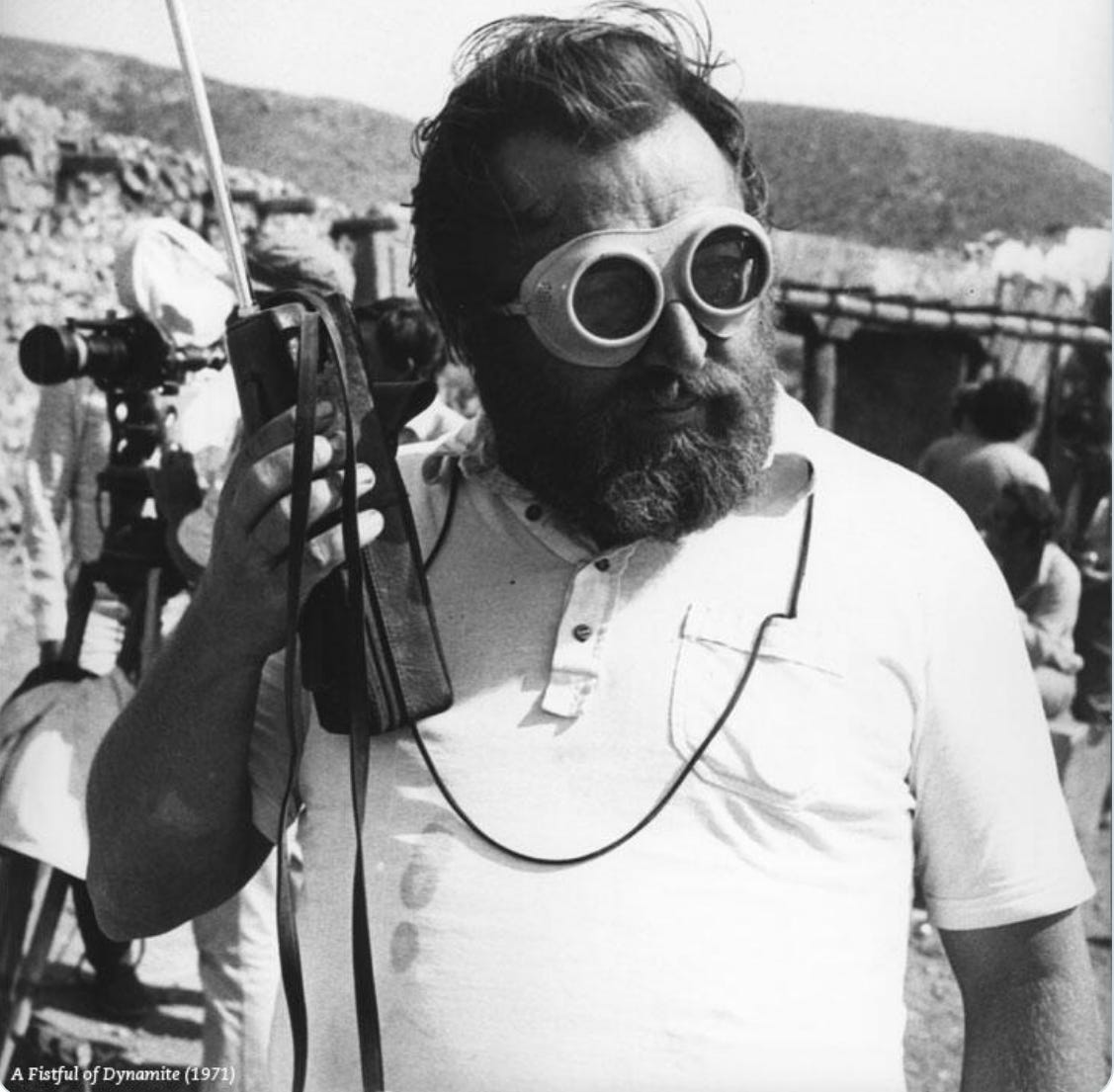

At a smaller round table in the corner sat Leone. He wore motorcycle goggles with a wide brimmed hat and rested his hands on his belly. At his elbow was Ennio Morricone, whispering continually in his ear. I couldn’t hear what he was saying but occasionally there would be a moment when the carriage stopped clanking at the same time as the wheels stopped screeching and we could hear faint singsong mumblings. At first I wondered if Morricone was reminiscing about the days when, as a child, he would play the french horn in a brothel to earn money for his impoverished family. But the more I watched, the more I felt that the composer was talking to Leone about me. Leone would nod every once in a while, as Morricone, in his thick-rimmed dark glasses, stared steadily at me.

I unwrapped a small piece of guanciale from its waxed paper, took my knife from my boot and began to cut the fatty, cured pig’s cheek into little pieces. Pieces for which the English don’t even have a name. Lardons in French. Tacos in Spanish. But not Mexican tacos, they’re something entirely different and there wasn’t a Mexican aboard. Unless you count Tuco and Rod Steiger who both played the part of bandits. But they were American.

All very confusing.

I set the skillet on low to render then crisp the guanciale. Using the hole at the end of the handle, I pinned the pan to the work surface with my knife.

A high-pitched whine made me turn to the table. Claudia Cardinale and Marianne Koch, eyeliner heavy, had joined the three actors. Both were dressed in dusty black, their darkened eyes shining, brimful with regret. I nodded a greeting that they both chose to ignore, their attention turned to the windows on the other side of the carriage. Perched in each, both with a boot raised to jam themselves into the frame, were Jason Robards and Charlie B. It was Charlie who was playing the harmonica of course. Suddenly wary, I swung round and sure enough found Henry Fonda leant in the corner of the carriage, his sparkling blue eyes murderous in his unshaven dark face. His hand rested on the butt of his gun, his finger tapping the cylinder. I scanned the room. All the actors rested their hands innocently at their waists. Except for Koch and Cardinale whose hands were worryingly out of sight amongst their dresses.

The carriage was getting crowded and I noted a distinct tension in the air. It didn't help that Morricone was still whispering to Leone, both men looking my way.

I went back to the tacos of pork cheek and found that they were now bathing in their own fat, the pan juddering slightly with the bumping of the train. I scooped the guanciale to one side of the pan and pooled the fat at the other. Into this shallow pool I dropped a lightly crushed clove of garlic and spent a happy minute or two watching it go golden. I was about to remove it when I caught Leone’s eye and thought better of it. He liked the garlic left in. Interesting.

I found a tin of tomatoes on the ledge above the hob along with a packet of spaghetti. Handy. And the pasta was that beautiful stuff, the colour of sand that still had a dusting of semolina on it. Not the crap that looks like each piece has been polished and wiped of any soul.

The cheek was ready but I now had a new problem. I couldn’t see how I could get the tin open without using my knife which was holding the pan in place. Removing it would put me at risk getting pork fat all down me.

The whine of the harmonica ceased and was replaced by an ominous funeral march coming from the pocket watch that Lee Van Cleef held open in his hand.

I felt my shirt stick to my back as I looked from the pan, to the knife, to the tomatoes. The pan, the knife, the tomatoes. I had to do something. The pan the knifethetomatoes. Thepantheknifethetom…..I grabbed the handle of the knife, raised it up high, thrust it down, pierced the lid and had the blade back through the hole in the handle before the tune had finished.

I had no time to rest on my laurels. Now I had to figure out how to continue to open this dirty sonofabitch tin of tomatoes. But the problem was solved when James Coburn stepped forward - where the hell he'd come from I had no idea - took a banger from his breast pocket and shoved it in the hole I’d made with the knife. Blowing on the tip of his cheroot, he lit the fuse and turned his head away.

There was a little bang and the lid came clean off.

I looked about. No tomato anywhere but in the tin. What a dude. I was about to thank him when he cut me off with a smile of massive gleaming teeth.

I tapped a sprinkling of the chilli flakes I travel with into the pan, gave it a second, and followed it with the tomatoes. Stirring the whole glistening mess, I brought it to heat quickly and turned it down to a slow simmer.

The actors pulled their hats down over their eyes or receded into their kohl and snoozed for half an hour.

Leone didn’t sleep. He remained with his head still tilted towards Morricone’s mumblings. But they weren’t mumblings I realised. He was humming a tune to the director. And every note was like he was taking a pot-shot at me.

Well, I’d show him. These spaghettis would be delicious.

But for all my bravura, it was quite unnerving.

Trying to take my mind off the disconcerting Italians, I stuck my head out of the window. Up ahead, at the end of a long long curve, I could see a wooden bridge crossing a wide canyon.

The air in my face was hot and dry so I got little relief. Even less, when I turned my head and saw a rising cloud of dust and realised the train was being pursued by a horde of riders. An enormous man, at the reins of a carriage whipped and shouted at the horses. Beside him stood another man with one boot raised on the seat and a rifle at his shoulder. Great. We were being chased by Gian Maria Volonte and Mario Brega.

Just what I needed. More Italians.

But maybe we would make the bridge before they caught us?

A tiny puff of smoke came from the rifle and a loud crack in the ceiling told me Volonte was firing at us. A thin beam of sunlight from the hole it left, shone down on the tomatoes and brought my attention back to the job in hand. They were nearly there. I would ordinarily leave them longer but Volonte was gaining and he too was clearly hungry. The situation was bad enough already but the thought of a hungry Mario Brega didn’t bear thinking about. He had beaten Clint half to death in each of the films they had appeared in together.

I seasoned the water and cooked the spaghetti for two minutes less than it said on the packet. I was about to put on my glove to get the pasta out when I saw there was a utensil the same shape as my clawed fingers. God knows what it’s called. Or if He doesn’t, the French would. So would the Italians I guess.

I lifted the pasta into the sauce and began to stir and shake and toss and stir and shake and toss.

I dipped my tin cup into the pasta water and was about to pour it into the sauce when another shot cracked through the carriage. It made a hole in the cup and the liquid emptied itself into the sauce.

I tossed the cup out of the window and went back to the stirring, shaking and tossing. I tried it for salt and then got the plates ready.

I poured the remaining water from the pasta pan over the plates to warm them, emptied them and took everything to the table. Not a moment too soon. Brega kicked open the door and Volonte barged in behind him. That astoundingly handsome man laid his rifle on the table and they sat down with Morricone and Leone.

Evidently they had reached us before we reached the bridge.

I served the spaghetti, offering parmesan, pecorino and a microplane that I’d also found but they looked at me as if I was the devil. I backed away.

Nobody said a word as the men ate. Now I understood where Leone got the idea for all the eating effects in his films – the close ups, the grotesque chewing, the sound of the slurping, gulping and swallowing.

As they ate, I noticed Clint and Tuco, both smoking, get up from the table and go to windows on either side of the carriage. The bridge was close now. They each lowered their windows, pulled sticks of dynamite out from their clothing and went to light them.

Two things happened.

First, Leone wiped his chops. A bit of a coup. He’d liked it.

Second, the door at the other end of the carriage was kicked open and Robert DeNiro and James Woods, dressed in double breasted gangster suits entered, their tommy guns blazing.

Brega was the first to get it. He took a shot in the head that jerked him backwards, and then brought him down, face first into his bowl of spaghetti.

By this time everyone had their weapons out and was firing. Bodies jerked and blood spurted. The last thing I saw was both Clint and Tuco take bullets and drop their fizzing dynamite. I watched the sticks roll across the floor, then blow the carriage and everyone in it to smithereens.

Written in Almeria. Driving around. Listening to Ennio Morricone

What a marvellous melée! A lesson perhaps to always travel with a box grater for pecorino ... and use as Rachel Roddy advises, on the vicious side.

... Then I woke up and it was all a wet dream